The Red Army Juggernaut?

Not what she used to be. Some take-aways from the Wall Street Journal article about Russian soldiers.

On July 24, the Wall Street Journal published an article that gives a ground-level view of Russian soldiers’ war in Ukraine, ‘Commanders Saw Us as Expendable’: A Russian Soldier’s View of the War. It is difficult, if not impossible, to reach any definitive conclusions based upon a single newspaper article with its relatively narrow focus about a war that has been going on for over three years (not even counting Putin’s 2014 seizure of Crimea) and has resulted in over a million estimated Russian casualties. The Journal does, however, give us a valuable glimpse into the life of a common soldier at the front. It shows that the Russian approach, at least as reflected in this article, is far, far below the standards adhered to by the U.S. military.

The extent to which the U.S. and others can draw conclusions from this one article is extremely limited, but it does provide some valuable intelligence about the state of the Russian military. It is one piece of a larger puzzle that our intelligence analysts will be studying.

Highlights of ‘Commanders Saw Us as Expendable’

‘Commanders Saw Us as Expendable’ focuses on the experience of a 27 year-old Russian volunteer, Mikhail . Struggling to make ends meet, he enlisted in the army after being lured by the promise of an enlistment bonus equal to almost two years of his civilian salary.

A week after finishing his basic training Simdyankin found himself on the front where the army was fighting “with brutal Soviet-style tactics that pay for small gains with a colossal loss in lives.”

A short time later Simdyankin found himself in Vovchansk, a key objective that was hotly contested. Promptly after his arrival he was dispatched, along with three others, to assault a nearby house held by Ukranians. Two of the four were immediately killed by machine gun fire. Simdyankin and the other survivor withdrew as best they could.

But there was another Ukrainian-held house that needed to be brought down. Instead of detaching so much as a squad of 12-15 men or even a small fire team, his commander sent Simdyankin, who was on only his second mission, and one other soldier to throw an “activated antitank mine” into the house. They were taken under fire before entering the house. Simdyankin was wounded and his companion was killed. Simdyankin was forced to hide under rubble for four days with no food and only one water bottle, before he was able to come out and link up with other Russians.

A short time later he and another soldier, Ivan Shabunko were tasked with going with four other soldiers to reinforce a group of Russians who were holed up in an abandoned factory complex that was surrounded on three sides by Ukranian forces. Only Simdyankin and Shabunko survived the short trip. The other four Russians were killed before they ever made it to the factory. The WSJ article describes the literally unlivable conditions in the factory, and I discuss some of them below. Please read it for full details of the unimaginable conditions in which they lived. This sums up the results:

Of more than 100 Russian troops who had set up positions inside the plant months earlier, . . . no more than 25 now remained alive, spread out across two buildings in the complex.

On the third or fourth day after their arrival, the Ukrainians assaulted the building where Simdyankin and Shabunko were housed. The commander in the other building had already surrendered. Simdyankin and the others then surrendered. Simdyankin’s face was badly burned in the attack

They then went into Ukranian captivity. The Journal describes the Ukrainians’ reaction to seeing them.

Some of the captured men’s faces and hair were so burned that one Ukrainian soldier involved in the operation said “they looked like they just had come out of an oven.” The Russians were given water and cigarettes, but they kept pleading for food.

Several days after his captivity Simdyankin was interrogated and allowed to talk to his wife. Take a look at the video below. Caution: The entire dialog is in Russian. My rudimentary Russian is not good enough to follow the conversations, but if any readers are more fluent in Russian than I, please free to add share some of it in the Comments (which I am opening to all subscribers).

Click on various segments of the video and watch them for just a minute or two. You will see someone who will be a broken man forever. The interrogator places a Facetime call to Simdyankin’s wife and turns the phone over to him to speak with her at about 42:50. Be forewarned: You may find it difficult to watch.

Here is Simdyankin with his sister and nephew in better times.

My take-aways

The WSJ article provides data that the military will evaluate along with much other data in forming its strategic picture of Russian military readiness and capabilities. It is limited but valuable data. Professional military analysts in the U.S. military will look at all of it with much more experience and expertise than I can bring to bear. But for the lay reader who may lack military experience, I offer the following observations. Each of these examples of the current Russian approach is in sharp contrast with U.S. doctrine and procedures. I respectfully submit that they reveal real weaknesses in Russian military preparedness.

Untrained soldiers are rushed into relatively heavy combat in just a matter of weeks.

Simdyankin’s basic training lasted all of two weeks. By way of comparison, before they are sent to their assigned units, U.S. Army soldiers undergo approximately five months of training: 22 weeks in Basic Combat Training followed by Advanced Individual Training. It is impossible to prepare soldiers adequately, even in peacetime much less for immediate combat deployment, with only two weeks’ training before they are shipped off to the front. As much as anything, this is a tell that the Russian army is not in good shape.

Front line infantrymen who significantly older than their counterparts in the US military

This is a long way from a reliable statistical analysis of the average age of a typical Russian infantryman, but I was struck by the ages of the soldiers featured in the article. Simdyankin is 27. Ivan Shabunko, who accompanied him in leading the four unnamed soldiers trying to reach the factory, is a 47. He joined the army to avoid going to prison. One of the soldiers they encountered when they finally managed to get to the factory alive was Aleksandr Trofimov, who was “in his early 40s.”

In the U.S., most infantry soldiers are relatively young men. That is because infantry combat necessarily is a young man’s game. Personal memoirs are replete with anecdotes describing how soldiers who were 24 or so were nicknamed “Pappy” and regarded as old men. In Vietnam, the average age of front-line infantryman in the Army (MOS 11B) was 22.5. For the Marine equivalent (MOS 0351) it was 20.4.

Perhaps Simdyankin’s unit was atypical, but if the ages reported in the Journal’s article are accurate and representative, Russia appears to be attempting to fight a young man’s war with a lot of not-so-young men.

Lack of logistical and medical support

I was appalled at the conditions in the factory that Simdyankin and Shabunko were sent to reinforce. Although the Russians tried to deliver supplies with drones, many were shot down. Relief convoys were not mentioned. Food was short. And bad. Potable water was so scarce that soldiers stole from each other.

Even brief forays outside the building in which they were sheltered were highly dangerous. Trofimov, the soldier described as being “in his early 40s” was wounded by shrapnel when he ventured outside “trying to salvage food.”

The wounded and dead were not evacuated. Even gravely wounded soldiers were left to fester and die a lingering death. Decomposing bodies were left to rot in the same small buildings as those still alive.

I will not dwell on the obvious by discussing how antithetical it is to the doctrine and of the U.S. Army and Marines.

Officers who don’t give a flying f**k about their men.

Simdyankin summed it up:

“Our commanders saw us as expendable. They didn’t care whether or not we survived.”

“Take care of the troops.” That is a mantra of U.S. Army leadership. But there is a delicate and complex balance between a military officer’s duty to accomplish his assigned mission while also taking care of the troops. Any combat commander knows that some of his soldiers may die because of decisions he must make and commands he must give to accomplish the mission. Good, well-disciplined troops also know that. But they also must know that the commander cares about, and will do his best, consistent with accomplishment of the mission, to see that they get home safely. The best commanders I know will tell you frankly that they “love” their troops. And those you love are not “expendable.”

But when the members of a military unit think that their commanders don’t give a flip about their lives, that delicate balance is destroyed. That doctrine of indifference to mass casualties is consistent with the Russian army’s reputation in World War II. But I submit that it cannot survive and produce good results in a modern, more open society, even one under the thumb of a totalitarian dictator such as Putin. It certainly would not work in the U.S. military. The Chinese and the North Koreans may still employ the same callous indifference to casualties, but we shall see whether it can be sustained even by a historically brutal military once more of its soldiers have been exposed to Western culture and ideas. I defer to the intelligence experts on that.

Russian units that lack unit cohesion and that can’t foster soldiers’ loyalty to comrades.

One of my big take-aways from the WSJ’s story is the lack of any evidence of effective combat leadership by Russian commanders. Each of the shortcomings described above can be attributed to a leadership vacuum. Leading an infantry unit in combat is not easy. It is not something that everyone is cut out for. But a key requirement for success is leadership that convinces soldiers that their commander is dedicated to taking care of them, even though he will be leading them into harms way. That cannot happen if the soldiers you ask to risk their lives think that the commander regards them as ‘expendable.’ I will elaborate slightly on this in the Conclusion below.

Conclusion

A critical part of effective combat leadership is developing unit cohesiveness — the camaraderie, the esprit de corps, the bonding — call it what you will, that enables and motivates soldiers to go forward under fire, to charge when others would flee, to put it all on the line. Why do soldiers fight? I divide my answer into two broad parts, individual loyalty and unit pride.

Soldiers don’t fight for God, country, motherhood and apple pie or even “Mother Russia.” They do not crawl through the mud under machine gun fire, bind up their wounds, and overcome intense moments of terror so that politicians can accomplish some political goal. They fight for each other. They risk and sometimes give their lives for other soldiers whom they may not even know. This loyalty is the glue that bonds soldiers into a successful unit that wins battles.

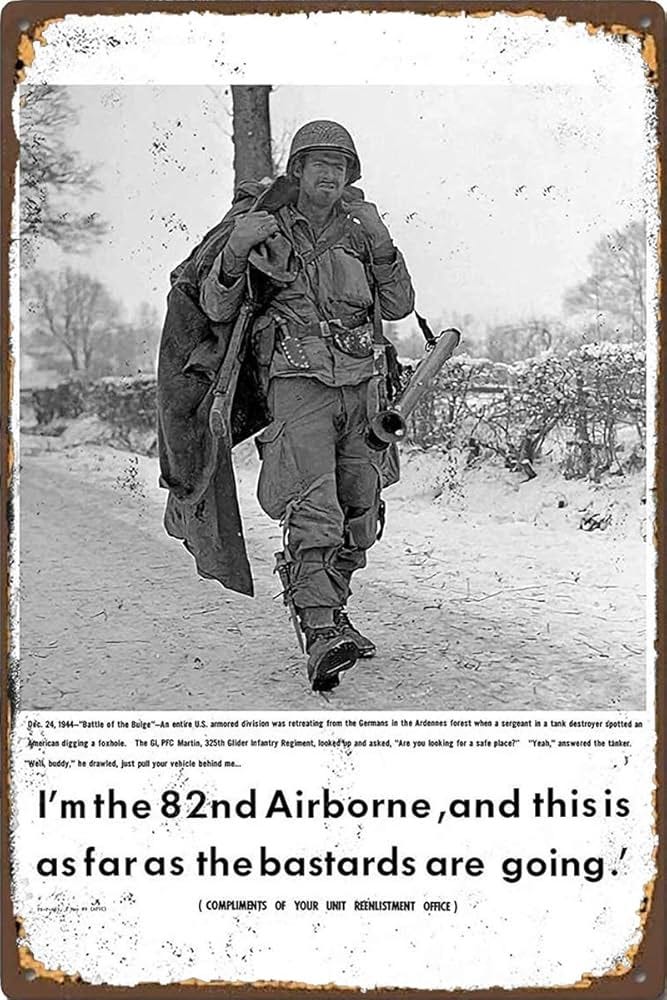

Part of that loyalty is to their unit as well as to their foxhole buddies. Many men fight because of pride in their unit and its history, whether it is a Marine regiment or an Army division. With that thought I leave you with this photo from the Battle of the Bulge in December 1944. Here you see a man who was not about to let down the 82d Airborne.

Good article John.

Hard to read, John. Hard words to read. You hate to see any soldiers anywhere treated as expendable. Getting your wounded out and back to a safe haven is a tenet the US has always had. In today's modern military, the ability to evacuate wounded is better than it has ever been. Such callous disregard for your troops is appalling. I wonder if the Ukrainians do better. Hopefully, Trump will make progress in his efforts to bring peace.