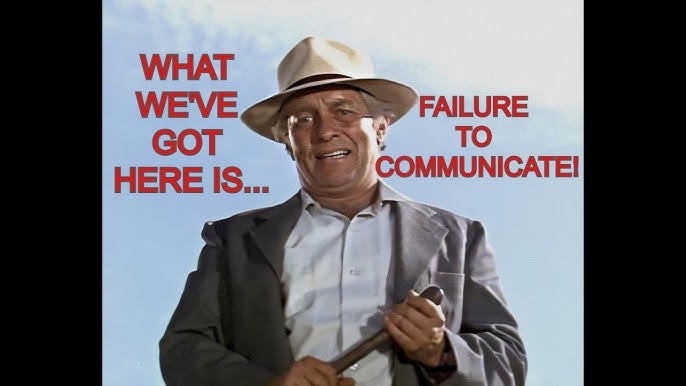

“What we've got here is failure to communicate.“

Beware of the risks of miscommunications with different cultures.

“Happy Boxing Day” to all my British readers and friends. Thinking today about Boxing Day and most Americans’ lack of understanding about it, caused me to think a bit more about the problems caused when people from one culture do not understand a particular word or phrase the same way that those from another culture do.

“Boxing Day” is plain English, whether it is said in Philadelphia or Liverpool. But a fighter in, say, a Philadelphia gym, might be forgiven if he thought that it had something to do with the day Mohammed Ali humiliated the fearsome Sonny Liston, or the day of Joe Louis’ epic destruction of Max Schmeling.

Americans not understanding Boxing Day is a minor thing in the panoply of problems that we must deal with. It is both understandable and excusable, perhaps akin to an Englishman’s failure to appreciate the difference between Memorial Day and Veterans’ Day. But the results of misspeaking or not understanding another culture’s word usage are not always so benign. Instead of something merely requiring a simple explanation, such a “failure to communicate” may result in something else, ranging on a spectrum from gross rudeness or creating a perception of giving having given grave insult, to downright hilarity.

One example of the former is a story that I recall hearing about a politician from the American South, who was invited to dinner at the home of a very upper-crust and quite proper British diplomat. When he was introduced to the charming young son of his hosts, the American is said to have patted the youngster on the head while complimenting him to his parents: “Cute little bugger, isn’t he?”.

As an example of the latter category – downright hilarity – I offer an anecdote from my own personal experience. Several years ago, I was invited to join a relatively small internet group that was comprised mainly of Brits with a small number of Americans. In the early days of my membership in the group, I was trying to learn something about each of the other members. I began to develop an electronic friendship with one particular Englishman through conversations via emails.

Here I must digress for a moment to explain something about my personal frame of reference and understanding of British terminology. In my younger days, I was a proud United States Army paratrooper. Back in those days, paratroopers were the heirs of the heroes who parachuted into Normandy on D-Day. Being admitted to that select group after three rigorous weeks in jump school, polished off with five parachute jumps, was a source of enormous pride for all of us. And there was a common bond between paratroopers from different countries. I recall meeting fellow paratroopers from other countries, and we immediately regarded the others as comrades.

The British have a very elite, very tough “Parachute Regiment.” But they use a somewhat different terminology to describe its members. They men in the Parachute Regiment are not called “paratroopers.” They are universally referred to simply as “Paras.”

Now, back to my story. During our budding transatlantic friendship, as we were getting to know each other my new English friend told me in an email exchange, “I am a para.”

As had been the case when I had previously met paratroopers from France and Finland, I was quite excited to learn that we shared this common bond. So, I emailed my new friend a quick response, doing my best to use his terminology so as not to offend. It went like this:

You’re a para?!! That’s great.! I am a para too. And many in my family are paras, too. My son is a para! And I have two nephews who are paras. We love being Paras!

His response:

I don’t think you understand. . . . I am a paraplegic.

So, what conclusions, what deeper truths, can I impart to you from this sad experience? I don’t have a clue. I cannot suggest any broad lessons to be gleaned from this. If there are any, I have not learned them. The only advice I can give is to try not to pat an English youngster on the head while telling his parents what a cute little sodomite he is. And try your damnedest not to tell a British paraplegic what a wonderful thing that is for him.

The IDF has paratroopers, Tzanchanim. They are an elite unit and jump or get pushed out of a C-130(?) six times on a static line. The instructors must speak to them in American English (if from here) and say, " make sure your chute opens after three seconds; if not, pull your reserve. Make sure to drop your ruck on the tether so it lands first. They wear red berets and boots like the paras you speak of. And one more thing. Anwar Sadat laughed out loud when told of Jewish paratroopers. That will be the day that Snakes fly! Their emblem? A snake with wings.

As a transplant from California to North Carolina, some neighbors invited me to dinner one Sunday. I showed up at 6pm. They were surprised to see me, having expected me just after church around 12:30. In the South lunch was dinner and dinner was supper. I've adjusted and now clarify the exact time I'm expected. Learning Southern has been fun, as they've learned Californian.