This is a story few of you have ever heard. It is a story of courage that required nerves of steel. As I think on this and others like it, I recall the movie, The Bridges at Toko-Ri (based on the book of the same name by James Mitchner). The book and movie are about Navy carrier pilots attempting to take out heavily defended bridges in North Korea. At the end of the movie, pondering the raw courage of the pilots who braved the fire and died, the Admiral in command asks, “Where do we find such men?”

The story below was authored by my friend, Pete Dencker. Pete has been a friend for almost 60 years. In 1970 - 71 we served together in the 1st Cavalry Division. Pete commanded the 1st Cav’s Ranger Company, H/1/75 Rangers. I was the Blue Platoon Leader (Bravo Blue) with Bravo Company, 1/9 Cavalry. Among other things, we were the QRF (quick reaction force) for the Rangers when the stuff hit the fan with the Rangers in the middle of it.

Some of you have read my prior articles about B Troop, 1/9 Cavalry. If you have not, please read them here (“Running Through the Fire”) and here (“Remembering a Little-Known Veteran”) to get some background about the story that follows. Among other things, they explain the “Pink Teams” and the “Blues,” discussed in Pete’s article.

For readers who may not be familiar with all the military terminology, I have added a few explanatory notes below in brackets. Otherwise, the article is Pete’s, with the exception of my concluding comments.

RANGER TEAM 75

So, here’s Pete:

RANGER TEAM 75, AUGUST 1971

On the afternoon of 3 Aug 1971, Team 75 of H Company (Ranger), 75th Inf., of the 3rd Brigade (Separate), 1st Cavalry Division was on a long-range reconnaissance patrol in Long Kahn province. The patrol was acting on specific intelligence concerning a possible sampan docking sight surveilled during a previous mission led by SGT Jim Faulkner (also of H Company), a notably successful Team Leader.

The patrol consisted of five American Army Rangers and one former Viet Cong Kit Carson scout. The team included Team Leader SGT Terry Wannish, Assistant Team Leader SGT Daniel J. DeMara, Jr, RTO SP/4 Wayne Okken, Rear Scout SP/4 James Dickman and Lt Mike Davidson.

SGT Wannish was walking point and saw numerous footprints in the mud on the side of a stream indicating a possible sampan docking site. The Team located a hide site on the opposite side of the stream in the heavy jungle about thirty feet from the stream bed.

Late in the afternoon, several sampans arrived at the docking site. Before dark, the Team counted 120 Viet Cong and/or North Vietnamese Army soldiers get off sampans and make camp near the bank on the opposite side of the stream. A number of enemy soldiers used the stream for bathing. The Team remained in their hide site throughout the night. Shortly after dawn, the enemy reloaded the sampans and left the area.

The Team then crossed the stream and set up an 18-claymore ambush on the side of the stream that the enemy had used the previous night anticipating that another group might come through that night. The Team concealed themselves in the dense brush in the center of their camp area about 40 feet from the stream.

The VC/NVA did in fact return that night in numbers similar to the previous night.

Company SOP was to make commo checks every fifteen minutes over the full time of deployment, day and night. During the night the enemy could be heard speaking in a normal tone of voice, and the Team, concerned about being compromised, suspended the normal commo check procedure, opting instead for breaking squelch twice if everything was OK.

The Team made a more complete situation report on the morning of 4 Aug after the enemy left the camp site and after the Team crossed the stream and moved back to their original hide site. At the time H Company was OPCON [under Operational Control] to the (1st Cav) Brigade S-2 and based on the reporting over the past few days, the Brigade staff began preparations to support a possible Team initiated contact that night.

The patrol area—a four click [kilometer] grid square with a surrounding one click buffer zone—was typically outside any US or ARVN [Army of Vietnam] artillery support. Air/ground fire support normally came first from an Air Force Forward Air Controller (OV-10 Bronco aircraft, who typically used the call sign “RASH”). RASH was airborne 24/7 and a Team could usually expect fire support within several minutes of a request. Helicopter gunship support from Blue Max 229th [Cobra gunships with 2.75-inch aerial rocket artillery] or Bravo Troop, 1/9th Air Cavalry usually arrived within 10 to 15 minutes. At that time the H Company rear was co-located with Bravo 1/9th at a Thai fire support base (Bearcat), southeast of Bien Hoa. The close proximity of this living arrangement was responsible for an intimate and important working and personal relationship between the Rangers and the 1/9th support units.

As night fell, a pink team (an OH-6 LOH [Light Observation Helicopter] and Cobra gunship) was airborne and masked beyond a nearby hill just out of range, to eliminate any aircraft noise prior to any impending contact. The Blue platoon of the Air Cavalry squadron, a heavily armed light infantry force, was on standby at the closest fire base. RASH, and everyone else, had the Team’s location plotted. The deputy brigade commander was airborne in his command-and-control Huey with the pink teams.

As light began to fade, once again a group of at 100+ enemy pulled into the same unload site and began to set up camp for the night. At full dark, SGT Wannish blew the clacker for the claymores located in the main camp area. Several minutes later, there was additional movement by the enemy and SGT DeMara blew a separate set of claymores on an avenue of approach to the right front. H Company SOP was to lie quiet after blowing the claymores to let the enemy think they might have run into an automatic ambush [a claymore mine ambush triggered by a trip wire, instead of a manual firing], a technique used frequently by regular Infantry units at that time. As the remaining enemy survivors and wounded began moving in the contact area, the Team used grenades which would not reveal any specific friendly location to the enemy, neutralize any additional movement and, at the same time, instill fear into any remaining survivors.

At that point the Team’s air support arrived on station. The AF RASH began rocket fire and machine gun fire. Bravo 1/9 pink teams brought in danger close 2.75-inch rocket, 20mm cannon and 7.62mm mini-gun fire. The ongoing relationship and mutual confidence between the Ranger Team and the 1/9th pink teams were instrumental in allowing for this very close-in air support.

After the air support had sufficiently worked the area, SGT Wannish, SGT DeMara and Lt Davidson had just begun to move into the kill zone to review the damage and look for any remaining survivors when the deputy brigade commander in the command-and-control aircraft, concerned about other potential large groups of enemy soldiers in the area, ordered an immediate extraction by McGuire rig.

The pink team aircraft were very low on fuel (One of the Bravo 1/9 Cobra pilots later explained that he landed back at the firebase with 2 minutes of fuel on board), and this created questions regarding the availability of fire support in the event additional contact materialized.

The Team was extracted by McGuire rig without further incident. The following morning, at first light, the Team returned to the contact site, accompanied by the 1/9th Blue platoon as security, to see what, if anything, could be recovered. Despite the enemy working through the night to remove bodies, wounded and intel, there were approximately a dozen bodies remaining (initial estimates of enemy KIA were multiple times that number, some estimates as high as 100+), along with numerous blood trails, body parts and a large amount of material that proved to be of significant intelligence value.

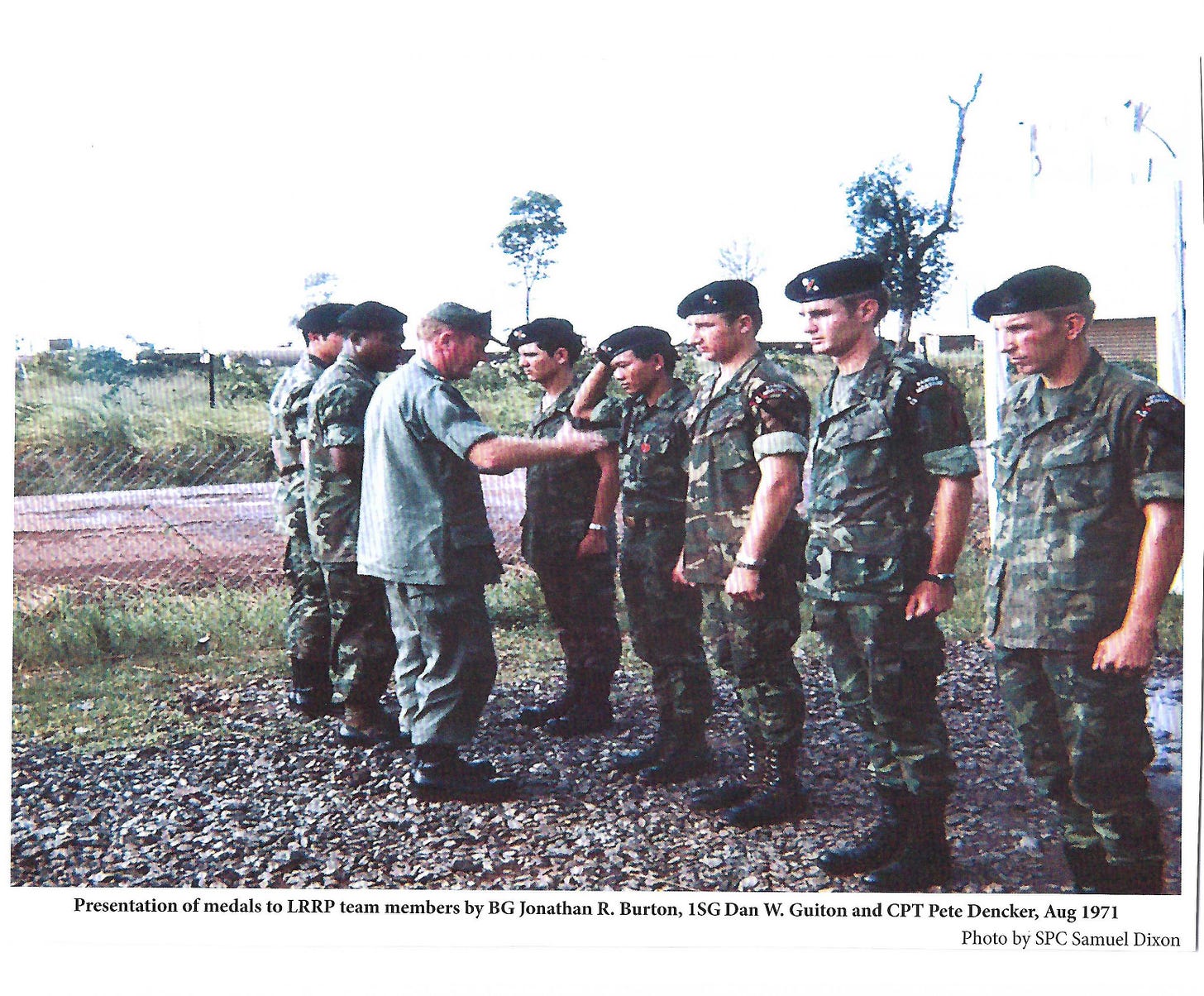

There were no friendly casualties. Sgt Wannish and his Team reported to the Brigade S-2 for a debriefing upon their return to Bien Hoa and subsequently received impact awards for their actions in August 1971. [An impact award is an award for valor or meritorious service that is presented immediately by a general officer, without waiting for the supporting paperwork to be completed.]

RLTW !

“For those who’ve fought for it … Life has a flavor the protected will never know.”

* * * * * * * * * *

Impact Awards Ceremony for Ranger Team 75

MY OBSERVATIONS

When you read an account like this, it is too easy to lose sight of the reality on the ground. So let me put this story in context. In 1971 when this action took place, the Country was still experiencing the turmoil that began in the 60’s. Unlike today, when “Thank you for your service” is ubiquitous, the military was not just unpopular, it was “loathed” by many.

THE TEMPER OF THE TIMES

The tone of the times is exemplified by Bill Clinton’s 1989 statement that what he called “many fine people” actually “loathed the military.” Clinton’s view was widely shared. Those of us who served still remember the demonstrations where the supposedly “elite” college students were supporting our enemies, waving the flags of those who were trying to kill us, while chanting, “Ho, ho, ho. Ho Chi Minh is going to win.”

It was in that sick environment that the men of H Company, 75th Rangers risked their young lives every day.

RANGER PATROLS IN THE JUNGLE ENVIORNMENT

Now try to reflect upon what these Rangers did in August 1971, and every day, and what it took for them to do it, especially given the lack of support by their countrymen. They could have taught the NVA flag-waving college students what “elite” really looks like. These Rangers typically were about eighteen to maybe twenty-two years old. They normally went out in a small group of five or six soldiers. These patrols were called “LRRP’s” for long-range reconnaissance patrols. They were long-range because they typically were operating beyond the range of artillery support. So, for fire support they had to rely on helicopters, which might not always be available because they were subject to the vagaries of the weather.

When a LRRP team made contact with the enemy, they might not know initially if they were up against ten men or a hundred or more. If it was a large enemy force, they would need to be reinforced immediately by the Bravo Troop Blues, but even then, the Blues might be a twenty-minute helicopter flight away. A lot can happen to a six-man patrol in twenty minutes.

Now try to imagine what it was like on those early August nights in 1971. The typical terrain is Southeast Asian jungle, occasionally cut by a stream or river. Visibility in the jungle often is limited to fifteen to fifty feet. That’s during the day. At night the visibility is about what it is in your closet at midnight with the door shut. As we all know, pitch-black darkness can heighten the fear factor. Especially when you know there are men in the darkness who want to kill you.

Now think about the length of time these young men had to think about what was happening and what was going to happen. On Day 1, they observe a force of more than 120 enemy disembarking from their sampans to set up for the night. Throughout the night the Rangers stay awake, knowing that they are just a short distance from a full enemy company.

The Team remains in their hide site throughout Day 2, but that evening they re-cross the stream and set up an ambush with claymore mines, forty feet from the stream. Now think about that – Picture yourself in a six-man team, forty feet from the stream, so you will only be fifteen or twenty feet from the enemy once they disembark and establish a position for the night. Another enemy force does arrive and again sets up for the night. Another almost-sleepless night passes and the Rangers remain hidden. But think about the stress they are under, knowing that they are outnumbered by more than 15-1 by enemy just a few feet away.

If they are discovered, they will die.

After that enemy force departs on Day 3, anticipating the arrival of another similar force, the young Rangers again set up for a night ambush. Close your eyes and try to put yourself in the place of those young men. You have just spent two nights just a few feet away from large enemy units and just before dark another 100+ man enemy force arrives for the night. You lie there, sleep-deprived, hoping that you will not be seen and that the NVA cannot hear your heart pounding. Then, after dark, your Team Sergeant initiates the Claymore ambush. Aircraft arrive, adding to the chaos by firing their rockets, cannon and mini-guns. Because the enemy force is so large, the Team Sergeant has the coolness and presence of mind to direct the aircrafts’ fire outside the claymore mine kill zone, to ensure than the enemy who survived that initial blast could not close with and kill the Rangers. And, need it be said, calling in aerial rocket and cannon fire just a few yards away, at night with scant visibility, is not for the faint of heart.

Many men die. Others are wounded. You hear them thrashing about and screaming or just lying there, groaning. Those alive are still armed and dangerous, even if wounded. That could easily be you if only the enemy had run security patrols around the area before nightfall. That it is not you is due to that failure, to your superb training, and to your and your teammates’ ability to remain calm and focused while under the stress and fear of possible imminent death.

General Sherman was right: “War is hell.”

McGUIRE RIG EXTRACTIONS

Pete’s reference to the Team being extracted by McGuire rig merits a short explanation. A McGuire rig is a harness suspended from a long rope, used for emergency extractions where there is not a clearing nearby that is large enough to allow a helicopter to land. With one end of the rope fixed in a hovering helicopter, the rig is dropped from through the jungle canopy to the ground. After the men get into the harnesses, while in a hover the pilot must raise the helicopter completely vertically until the men are clear of the trees. Only then can the aircraft begin forward movement. If the pilot does not raise the helicopter, and the men dangling from the ropes, straight up with no forward or lateral movement, it becomes even more dangerous because the men hanging in the McGuire rigs will be dragged through the trees. This is difficult enough but during the day but at night the danger is off the charts.

RANGERS LEAD THE WAY

Pete’s concluding “RLTW” may require a short explanation. On D-Day, June 6, 1944, Brigadier General “Dutch” Cota was the assistant division commander of the 29th Infantry Division. The 29th was National Guard outfit that was seeing its first combat in the Normandy invasion. Cota and the 29th went ashore on the deadliest section of the beach, code-named Omaha, where the Americans suffered 2,400 casualties in just a few hours. Cota was personally directing the attack, but the slaughter was devastating. As related by the Pennsylvania National Guard Military Museum, Cota was trying to motivate frightened and shell-shocked men into advancing into the deadly fire when he encountered a group of men and asked their commander, “’What outfit is this?] Someone yelled ‘5th Rangers!’ To this, Cota replied ‘Well, goddamn it then, Rangers, lead the way!’” The Rangers then did lead the way in the successful attack to reach the heights above Omaha Beach and “Rangers Lead The Way" became their motto. Now abbreviated to RLTW, it is a frequent exhortation among Rangers, both when speaking and writing.

EPILOG

Pete Dencker was my West Point classmate, where he was a standout Army football player. Before taking command of the 1st Cavalry Ranger Company, he served as a lieutenant with 1st Battalion, 7th Cavalry where he was wounded and awarded a Silver Star Medal for gallantry in action. He was on the helicopter that performed the McGuire rig extraction of Team 75. After getting out of the Army, Pete founded a successful construction company in Tennessee, where he now lives. He is a subscriber to this Substack account.

Then-Lieutenant Mike Davidson also is a subscriber to this Substack. Before joining the 1st Cavalry Ranger Company, Mike earned his green beret as a Special Forces officer. He also served with 5th Special Forces Group after his Vietnam service. Among other decorations, Mike was awarded a Purple Heart, a Bronze Star Medal and an Army Commendation Medal for Valor. Mike ultimately retired as a Major General and makes his home in Kentucky.

In searching for a suitable conclusion that does justice to the courage of these young Rangers, I found a quote by President Reagan. I cannot possibly improve on it. President Reagan said: “In James Michener’s book ‘The Bridges at Toko-Ri,’ he writes of an officer waiting through the night for the return of planes to a carrier as dawn is coming on. And he asks, ‘Where do we find such men?’ Well, we find them where we’ve always found them. They are the product of the freest society man has ever known. They make a commitment to the military—make it freely, because the birthright we share as Americans is worth defending. God bless America.”

God bless America and RLTW.

The line “Where do they find such men” has so much more meaning today. Every decade that passes there are less and less of these men that would qualify to do what the soldiers of the past did. Not saying there aren’t some, but the pickings would be slim.

Another great post John. Thanks for sharing.