The Battle of Antietam, on September 17, 1862, was the bloodiest single day in American military history. On Saturday, September 6, I was returning home after revisiting history by walking the Antietam battlefield with friends. To enjoy the scenery and relative peace, I purposefully avoided interstate highways on my return trip.

As I was driving along a rural road in Culpeper County, Virginia I had the good fortune to stumble upon an intriguing piece of American history. I spotted what appeared to be a veteran-type headstone marked with a U.S. flag. Here is a view from the road.

I was intrigued to see a solitary grave with a with a military headstone out in the middle of nowhere. There were no houses or businesses anywhere in sight. It was a very rural area without any nearby tourist attractions or other tourist attractions. Not a place where I expected to see a veterans’ cemetery or even a solitary grave.

The town of Remington (2025 population of 658 souls) is a short distance away across the Rappahannock River. It is a very rural area with few nearby houses and other infrastructure. Here is an aerial view of courtesy Google Earth.

Intrigued by the glimpse of what I saw as I was driving by, I turned around at the first opportunity a short distance down the road (at the intersection of Rte. 673 on the above image) and drove back. When I got out of my truck to look, this is what I saw.

Wow! A captain, a Son of the Revolution, who also was a veteran of the Indian Wars, buried in 1813 at a roadside in the middle of this sparsely populated rural area but without any of the customary road signed to alert travelers as to who he was or what he had done. But someone more recently had remembered him with a military headstone and bronze discs including one from the Sons of the American Revolution.

I could not help but wonder, who was this Captain Francis Hume and what of his life? This is what I found when I got home and spent a little time researching him and talking to people in Culpeper County.

The Hume family in Scotland back the wrong side in a rebellion

Francis Hume was the son of a Scottish immigrant George Hume, who was born in Wedderburn Castle in Scotland in 1698. As you can see, it was a rather upscale home as befitted Scottish nobility in the 17th Century.

The Hume family supported and participated in the Jacobite Rebellion of 1715. The Scottish Jacobites were followers of the descendants of James VII, King of England, Ireland, and Scotland until he was deposed and exiled in 1688 as a result of the Glorious Revolution. Their aim was to restore the Stuart Monarchy and James VII’s descendants to the throne.

The Humes and other Jacobites failed in their quest, were stripped of power, and had their lands confiscated. Some were exiled, and still others were killed. George’s life was spared but he languished for two years in an English prison and was deported to Virginia in 1721. He settled in what is now central Virginia (then considered part of the Northern Neck) and became a successful surveyor. Among other things, he surveyed and laid out the plans for the City of Fredericksburg, where he married Elizabeth Proctor. Fredericksburg, of course, was to be the site of another terrible bloodletting in the American Civil War, less than three months after the Battle of Antietam.

Francis and his military service

Elizabeth gave George eleven children, all sons (how Anne Boleyn would have envied her!), including their second son, Francis, in 1730. Francis may have been named after one of his contemporary family members, Captain Francis Hume, who became a Captain in the English Navy even though he was a Scot who was born in Germany and spoke little English. Naval Captain Hume made his bones captaining HMS Scarborough, a 32-gun frigate, hunting pirates in the Caribbean. His is quite an interesting story that you can read here.

Francis ultimately became a farmer, near the present-day town of Culpeper. I located a copy of a deed made by Baron Thomas Lord Fairfax, “Proprietor of the Northern Neck of Virginia” granting him 609 acres of land in Culpeper County in 1760.

Records show that his first military experience was as a member of a militia company raised in Culpeper County by Colonel John Fields in August 1774. Fields, known as “one of the most prestigious men in the county” was a brother-in-law of George Rogers Clark, who was both the highest-ranking Patriot military officer on the Northwestern Frontier and the brother of William Clark of Lewis & Clark expedition fame.1

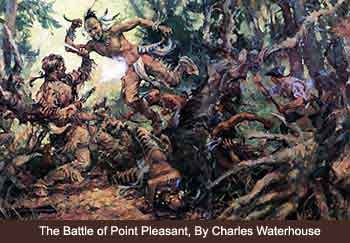

Francis and the other men in Colonel Fields’ 40-man company were to march west to join a larger group of several hundred men under the command of Colonel Andrew Lewis. Lewis had been ordered by Virginia's Governor, John Murray, 4th Earl of Dunmore, to march on Indian Nations in what became known as Lord Dunmore’s War. The hostile Indians were principally from the Shawnee tribe and had been attacking white settlers in a series of uprisings along the western frontier in what is now West Virginia and Ohio. The often-bloody dispute was over rights to land in the Ohio River valley.

Francis and the other Virginia militiamen marched all the way across present day West Virginia. On October 8, 1774, they arrived at a site known as Point Pleasant at the conjunction of the Ohio and Kanawha Rivers. The next night an estimated 600 - 700 Indians had crossed the Ohio river in over 70 rafts without being observed. The next morning, they attacked the Virginia militia at Point Pleasant, expecting to win a quick victory. That was not to be. The battle lasted all day and included up-close, hand-to-hand fighting. Colonel Fields was killed early in the fighting.

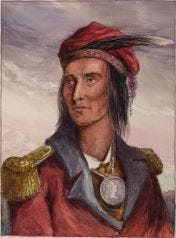

By that evening the Virginians had lost about 75 killed and 140 wounded. Although the militiamen counted at Shawnee corpses, a full accounting of their losses was impossible because the Indians evacuated their wounded and threw many of the dead into the river. Among the dead identified was Pucksinwah, the father of the famous Shawnee chief, Tecumseh.

As was customary at the time, scalping corpses (and sometimes living wounded) by both sides was commonplace, and both sides took their share of scalps. Colonel Fleming wrote that the Indians, unwilling to allow their enemies to brandish their bloody trophies, “Scalpd many of their own dead to prevent their falling into Our hands.”

By the time that Francis returned to Virginia in early 1775, the rebellion against King George III was gaining steam. Following the British Marines’ nighttime removal of gunpowder from the public magazine at Williamsburg, the colonists organized new militias to take on the British.

Not a great deal is known about Francis’ service in the American Revolution. What we do know is that he enlisted in the Virginia Continental Line. The state Continental Line units consisted of companies and regiments raised to meet quotas for each state set by the Continental Congress. Other Revolutionary War regiments were raised directly by the Congress.

We know that Francis’ service was honorable. He was discharged as a captain and received a “bounty warrant” of land in Culpeper County “for Revolutionary Services.” In addition to the Sons of the American Revolution, he was a member of “The Society of the Cincinnati,” which is the nation’s “oldest patriotic organization, founded in 1783 by officers of the Continental Army who served together in the American Revolution.”

Francis and his wife made their living farming in Culpeper County until his death in 1813 at the age of 82 or 83. They had ten children of whom eight were boys.

So that is the story of a little-known soldier from the 18th Century whose solitary grave I happened upon just because I chose to avoid well-travelled thoroughfares. It the visit and the time researching his story was time well spent.

Afterward

A hat tip to the Culpeper Minutemen, a chapter of the Sons of the Revolution, who located Francis’ 200+ years-old grave, erected the marker, and who apparently take the care to maintain it.

They placed the headstone and dedicated it at a small ceremony in 2005. Those attending included at least six of Francis’ surviving descendants. He was honored with the sounding of Taps by a bugler from the local Stonewall Jackson High School.

RIP Captain.

And a final note and request to readers

This article is a bit different than my usual posts of late. For me it is a welcome break from the ubiquitous fighting, both political and kinetic. If you enjoyed this and want to see more in addition to analyses of current issues and events, please let me know by hitting the “Like” button. That feedback will be important for my future planning.

And as always, please re-post on your other social media and forward to your friends.

An earlier version of this article incorrectly identified George Rogers Clark as a member of the Lewis & Clark expedition. Thanks to the input from another West Point graduate and subscriber who privately informed me that my memory was incorrect, the current version reflects his welcome correction. As we used to say, Bob, “Pop your chest up and take big bites.”

Bull Run is fascinating. But there are countless other metals that occurred in Virginia that most people don’t know anything about. I enjoy seeking out those sites.

Fascinating story, and superb research. Thank you, Bravo Blue!