This Christmas Eve and Christmas Day, I want to honor three strong men whose examples have given me a bit of courage and resilience when I needed it. None of them had any idea that they were filling this role. But particularly now I want other people who may be in need of a similar boost to know of their examples. For reasons that I will describe (briefly) below, the past couple of years have been a bit of a . . . . challenge, for lack of a better word. But during the rough patches, I would reflect on the experience and strength of three particular men. They all gave me a tad of courage and resilience and removed any temptation to even think about feeling sorry for myself. Perhaps they will for you, or for a loved one, or someone you know.

I am publishing this on Christmas Eve because it in the ninth anniversary of live- saving surgery for one of the three.

A Green Beret

I have never met Nick Lavery. I first heard of him when my son was commanding 3d Battalion, 5th Special Forces Group. Nick was one of the Green Berets in his battalion.

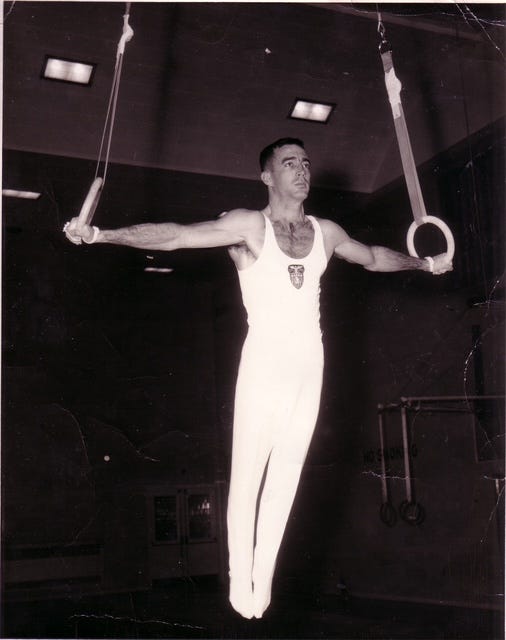

Nick is the first and probably only Special Forces soldier to return to ground combat after suffering an above-the-knee amputation. Here he is in Afghanistan after his recovery.

On Nick’s first deployment to Afghanistan in 2011-2012, he was wounded twice. The first time a rocket-propelled grenade “blew a lemon-sized hole” out of his shoulder. Despite that wound, he initially refused evacuation before he was finally evacuated to Bagram Air Base where he could get full medical treatment.

Nick was wounded again only about a month later. After his commander’s truck was hit with a roadside bomb, Nick ran forward to help. On the way, he killed two of the enemy and was pursuing a third when he was shot in the face. But that did not stop him from pulling his 6’ 6” 300 lb. commander (who had been an offensive lineman at West Point) out of his burning truck as the ammunition in it was cooking off.

Nick deployed to Afghanistan a second time in 2013. This time his luck nearly ran out. He and his Special Forces “A” Detachment were training local Afghan forces when a rogue Afghan policeman opened fire on them with a machine gun. Several team members, including his new commander, were killed. Nick was hit in the leg and his femoral artery was severed, setting the stage for a quick trip to the morgue. Nick applied a tourniquet to stem the blood loss. But it took over an hour for a medevac helicopter to arrive to evacuate him and the other wounded.

When he arrived at Bagram, Nick was almost dead. He went immediately into the first of 20 surgeries at Bagram before he began the long road to recovery. He was later transferred to Walter Reed Hospital. Before the doctors there were finished with him, Nick had endured more than 30 surgeries.

Nick’s story should not be reduced to just a few paragraphs. See more here and here. And he has been a guest on several podcasts, such as Danger Close and Jocko Willink. Take a look.

But what inspired me was not just that Nick performed heroically and recovered from his wounds. It was how he came back. Prior to his wounding Nick was a real physical specimen. He was incredibly fit at 6’ 5” and 270 lbs. After the loss of most of his right leg, he weighed 220. This was a man who had been totally focused on physical fitness, only to have his body blown apart in a way that few have survived, much less come back as strong as Nick did.

I am sure that Nick had his “down days,” but he fought back. As shredded as his body was, he passed the rigorous Special Forces fitness test annd was accepted back into his SF Group.

After his recovery, Nick did at least one more combat deployment to Afghanistan where he engaged in full Special Forces combat operations. He was the first above-the-knee amputee to return to accomplish this. He also completed several other Special Forces qualification courses that are not “gentlemen’s courses.” No one can accomplish this if they are wallowing in a state of depression or feeling sorry for themself. It requires focus, courage and commitment. Nick did it because he had made up his mind “that I wouldn’t be satisfied with just staying in the Army or staying on active duty. I had to go back to the exact same lifestyle I just left, and it was non-negotiable for me.”

An Appalachian Surveyor

In 2015 I represented an unforgettable client, Jim Reed. Jim was a surveyor who worked in upper East Tennessee, in the heart of Appalachia. Jim and his family own property near Oneida, Tennessee that sits atop a gas field. There was a dispute over who had the right to mine their property. Jim and a partner had been sued by some unscrupulous operators who basically were trying to steal their right to profit from the sale of the gas pumped from their property. Trying to get as much leverage as possible, the plaintiffs dressed up their claims as a federal RICO1 suit against Jim and his partner. Doubtlessly, they hoped that the massive costs of such a complex suit combined with the risk of losing and having to pay treble damages and the plaintiffs’ attorneys’ fees, would force a capitulation and settlement.

Jim and his partner did not cave. They prevailed. The details do not matter here. What I remember most was not the details of the case, but how smart and how tough Jim Reed was.

In my career, I have represented or cross-examined a number of high-profile litigants, including CEOs of major public and private companies, former cabinet officials, a few honest-to-goodness billionaires (back before the tech industry began churning out billionaires by the dozens), nuclear physicists, anti-trust economists, and other pretty bright and driven people. But not a single one was as smart as this plain-spoken Appalachian surveyor. No one else I ever represented or cross-examined was as prepared or had a better or more detailed grasp of thousands of documents as was Jim. Not one.

But my most powerful memory of Jim was his toughness in the face of adversity. With all the pressures of defending the potentially ruinous RICO suit, he was simultaneously suffering from cancer. He regularly (twice a week, I think) underwent both radiation and intravenous chemotherapy treatments. Then, after leaving the hospital wrung out from his treatments, he would go home, change into his work clothes and go out in the field to do his surveyor work, tramping through the woods, rocks and high grass. It was tough, hard work. It also required constant mental focus on the precision necessary to complete a survey of building lots or undeveloped land. It was — and is — almost inconceivable to me that he could pull it off after being subjected to the double-whammy doses of both chemotherapy and radiation. Anyone trying this had to be one tough hombre to pull it off. Jim was and did.

When I asked how he kept up his super-positive attitude and worth ethic, Jim had a simple answer: “I don’t like getting beat at anything.” But that determination was only part of the solution. When he went to the chemotherapy treatment center, he often sat next to a balding 10-year-old boy who was undergoing the same chemotherapy treatment. Both sat there for an hour or more with chemotherapy IVs in their arms. I can think of few things more heartbreaking than young children with cancer undergoing chemotherapy. Jim observed the boy on numerous visits and often talked to both him and his mother. He told me that the youngster never complained. Not once.

From this young boy’s courageous attitude, Jim took a lesson: “If he didn’t complain, then I shouldn’t either.” And that lesson from a terminally ill 10-year-old gave Jim the courage and determination to go home each day, change clothes, go to work, and never complain. He added, “I was not worried about me … me … me. I was only worried about my family.”

A Virginia Farmer

Gary Palmer, from Beaverdam, Virginia has a story similar to Jim Reed’s. And for full disclosure, Gary is my wife’s brother.

Gary had been suffering from a relatively rare liver disease known as Primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC), since late 1999. By 2015 complications had developed and Gary was diagnosed with Stage IV liver cancer. The cancer had metastasized to his lymph system, which often is a precursor of death.

On Christmas Eve, 2015, Gary underwent 13 hours of surgery for his cancer. Although he had great doctors, the outlook was bleak. When he went into surgery, Gary did not think that his chances of surviving were good. He survived the surgery but among other things, the doctors removed 60% of his liver. The succeeding years have been rough.

But Gary did not sit around moping and feeling sorry for himself. As soon as he was able, he went back to work farming. Although he is still at risk today, he says that “work was a saving grace. It kept my mind off my problems and on my work. It kept me sane.”

Today Gary’s doctors describe his recovery as a “miracle.” Not many people survive PSC that develops into Stage IV cancer, and then stay cancer-free for nine years after surgery. He is now on a list for a liver transplant.

The common thread

So why have I found these stories inspiring and why have they been a source of strength for me?What follows is my own abbreviated personal story that I relate here only to show how these three men have helped, even though they never knew it.

In the past two years I have battled two separate cancers, radiation treatments for both, and several undesirable side effects. NOTA BENE: I mention this and any anything related to it not to seek a grain of sympathy, but only because it is germane to the point I wish to make. In the U.S. over 600,000 and estimated deaths from cancer for 2024 are over 600,000. For Europe the figure is 1.9 million and worldwide it is almost 10 million annually. So, as I tell people when answering the inevitable questions about how I’m doing, I point out that I am not experiencing anything that literally millions of other people have not gone through.

With that disclaimer, let me add that some of the inevitable side effects have been a bit challenging and I had at least a couple of nights when I was happy to see the sun the next morning. I tried to remain positive at all times, but when going through something like this it probably is inevitable that sometimes you will get a bit discouraged and think “Woe is me.” Or, as Linda Ronstadt put it, “Poor, Poor Pitiful Me.”

This temptation to weakness may be particularly inviting to someone who has always been active and takes pride in physical fitness and activity, and their injuries or cancer take their inevitable toll on the body. That is hard to accept and adapt to.

But whenever I was even tempted to feel sorry for myself, I thought of Nick Lavery and everything he endured. So much more than 99.9% of us. Or of Jim Reed, a country surveyor who endured both chemo and radiation treatments and then went to work without a complaint. Or my brother-in-law, Gary, who came so close to dying from cancer but who showed enormous strength and never complained once.

I often thought of these men and reminded myself that if they could perform that well after going through so much more than I have, then I better get my act together and forswear any whining.

I owe them a lot.

Merry Christmas and a Happy Hanukkah to you all.

Bravo Blue

RICO (“Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act”) was originally designed and intended to be used to go after mobsters such as the Mafia and, more recently, organized drug traffickers. It requires proof of, among other things, a “pattern of racketeering activity” that is related to a defined “enterprise,” such as a Mafia family or a drug cartel. It can be used both in civil lawsuits and criminal prosecutions. Successful plaintiffs in a civil RICO suit can recover treble damages and attorneys’ fees. RICO suits are very complex and expensive both to bring and to defend.

Thanks; a good entry, this .

Sitting in a chair receiving IV drugs, as a beautiful child with her familyin attendance was undergoing IV chemotherapy next to me, provided me with a similar experience.

You have a very good Christmas.

M R Weiss, MD

Great stories of everyday heroes at a perfect time to remind us of the gifts we often take for granted.